Tucson, Arizona

It was somewhere back in 1975 when the phone was ringing. I was barely tall enough to answer it. It was mounted to the doorway of our kitchen, right next to notches our mom made to show us how much my little brother and I were growing.

I pulled down the receiver and put the phone to my ear.

“Hell-lo”? I said.

“Mr. Cauthorn is an S.O.B.,” was the reply, and the connection went dead.

I was too young to know what those initials actually meant, but I was acutely aware of the hostility on the other end of the line and the cowardly shame the crank caller may have felt after delivering their nasty payload to a child.

I was also aware that my father, Robert Cauthorn, wasn’t too popular at that time. A city council member, he had recently had contributed to a resolution that increased the water rates for people living in the foothills of Tucson. Many cities in the Southwest such as Tucson faced challenges not only in terms of water supply, but also the logistics of transporting water to higher elevations. This feat required extra energy and engineering, and the Tucson City Council members decided that this challenge warranted charging higher water prices to those living in the foothills.

But in general, residents in the foothills tended to be more affluent, and therefore more formidable when it came to protesting council measures that they didn’t like. The protesters weren’t even interested in arguing the point, they simply wanted to kick my dad and several other council members out of office. A man by the name of Fitzgerald led the whole, tea party-esque movement with the help of a connected lawyer. Fitzgerald (I forget his first name) was known as “The Color TV King” and sold them on the corner of Grant and Campbell avenue. I believe the sign is still there, as it may now be registered as some sort of landmark.

The Color TV King was in fact successful in throwing my dad out of office via a council recall. The council members scattered to the four winds. My family ended up in Florida very soon after. This ended being a positive development, as my dad was tired of getting a near poverty level salary while enduring the protests of people who either didn’t understand the rationale behind the water rate increase, or just didn’t care. To this day, Tucson foothills residents pay the same for their water as those that live down in the city. It basically amounts to taxpayer subsidized water delivery.

That bitter episode marked my first encounter with water supply issues in the Southwest. But that was just the beginning. A different type of water issue was rumbling on the horizon. It was brought on by population increases that were putting an increasing strain on the limited underground water supply. Golfing resorts like La Paloma and Canyon Ranch sprouted up and compounded the problem, as golf courses require tremendous amounts of water to be maintained.

These issues weren’t limited to Tucson. Las Vegas residents fought with California farmers for rights to the Colorado river. Farmers needed the river to water the Imperial Valley, some of the most fertile land on earth. Las Vegas needed the water to enable continued city growth. These were both perfectly good reasons to tap water from the river, but it didn’t matter how good the reasons were. There was only so much river. And nowadays if you travel to where the Colorado river naturally flows into the Gulf of California, you’ll find only dry sand. Fish species such as the Colorado Pikeminnow, one of largest species of carp in North America, are now effectively extinct in Arizona, Mexico and Nevada, and only found in the Colorado River headwaters in the state that gives the once mighty river its name. And in water starved Texas, tense negotiations continue with its northern, water rich neighbor Oklahoma. Texas may have oil, but you can’t drink it.

Please forgive the didactic tone for a moment. The term carrying capacity of a given environment is roughly defined as the amount of sustainable life it can support. How much food is available? How much water ? These variables have dictated where populations – both animal and human – have been able to settle in the past. But modern technology and engineering can now enable us to proliferate in areas where natural circumstances would previously never allow, effectively cheating the limitations of carrying capacities. We can turn deserts into golf courses, bring green Eastern style grass lawns to formerly rocky front yards, and pipe more water to new families who move to desert climates. But the water cost of doing this is huge, and it’s a game of diminishing returns. Now it’s no longer a matter of simply raising the water rates. It is getting to the point where cities like Tucson are in danger of running out of local water completely. Have we ever documented a situation where a large town simply runs dry? I don’t know, and certainly don’t know the solution beyond common sense conservation.

I also suspect that as Tucson’s water table drops, particulates and contaminants become less diluted and more noticeable, perhaps even dangerous. Polychlorinated Biphenyls, or PCBs, have been found at certain well sites in Tucson. I now live in Chicago, and am used to drinking the fairly good water that comes from Lake Michigan. I recently travelled to Tucson to visit my parents. My friend Jeff gave me a ride from the airport. We stopped and had lunch at a wonderful Mexican restaurant on 4th avenue. But when I took a drink of the water, it tasted like jet fuel. “What are you talking about?” my friend Jeff responded. “The water tastes fine.” And he proceeded to gulp down half a glass, looking at me like I was a lunatic. “You look so worried,” Jeff said.

But why should I be worried, I thought. All we have to do is negotiate with San Diego to construct a desalinization plant, and then run 400 miles of pipeline from the Pacifc to Arizona. We can pass on the gargantuan energy cost of desalinating and transporting this water to the Arizona taxpayers. They’ll understand, because the water must flow. Man – aren’t I a chip off the old block ?

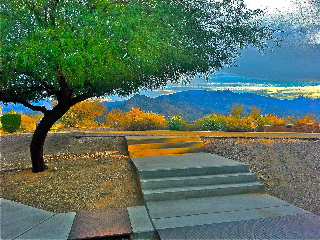

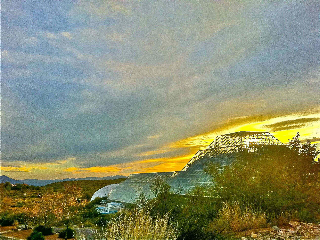

November 11th; after a warm reunion at Lynn Morton’s place in Tucson, Mel Dominquez, Bently Spang, and I are driving nearly a year to the day later in John Newman’s van loaded with food supplies north to Oracle and Biosphere 2. We arrive at 5:30 on a beautiful slightly cool evening and see Biosphere 2 with the glow of the sun’s last light illuminating the other worldly glass structure beyond the now familiar casitas where we will stay for the next week. Ellen and Phillipe are also there and we begin unloading our supplies.

November 11th; after a warm reunion at Lynn Morton’s place in Tucson, Mel Dominquez, Bently Spang, and I are driving nearly a year to the day later in John Newman’s van loaded with food supplies north to Oracle and Biosphere 2. We arrive at 5:30 on a beautiful slightly cool evening and see Biosphere 2 with the glow of the sun’s last light illuminating the other worldly glass structure beyond the now familiar casitas where we will stay for the next week. Ellen and Phillipe are also there and we begin unloading our supplies.

The week goes relatively smoothly (there are always glitches) and with cooperative indeed collaborative work on everyone’s part Saturday arrives and an impressive show by six artist’s emerged as a voice joining with the researchers from The Institute of the Environment in raising awareness of climate change. Joaquin Ruiz director of Biosphere 2 spoke eloquently about the close relationship between art and scientific research and we are all feeling enormously proud of our participation in this historic moment.

The week goes relatively smoothly (there are always glitches) and with cooperative indeed collaborative work on everyone’s part Saturday arrives and an impressive show by six artist’s emerged as a voice joining with the researchers from The Institute of the Environment in raising awareness of climate change. Joaquin Ruiz director of Biosphere 2 spoke eloquently about the close relationship between art and scientific research and we are all feeling enormously proud of our participation in this historic moment.