the book is the gutter. In the unlikely event of a water landing and

your book being submerged, water would collect in the gutter. The

pages would soak through and fall apart given time. The glue would

dissolve. The stitching would rot like a long-submerged body in a river

or a lake. By this point either you would have survived or you’d be

falling apart. The binding would then fall into its component pieces,

ruining the illusion of the artifact’s wholeness you’re holding. What

is in your hands is just paper, collected, printed on. What you are

holding is just ideas and language—the usual interlocking systems of

signs—printed on paper. It is not engineered to channel or hold water,

but it can do so in a pinch.

much of the year. It once did, and like many modern things—like

the trains in Upper Michigan, my homeland; like Western Union’s

telegram service; like the pinching of my childhood cheek by tottering

relatives; like the streetcars in Grand Rapids, Michigan, or most other

American cities; like the increasingly anachronistic telephone cables

strung all along our highways into the second-largest engineering

project after the interstate system; like the blood through the bodies

of our forebears, our betters, our mothers, our fathers, now dead; like

the language recognition centers in my brain that fail now to bring the

words I want to mind or tongue at awkward moments; like the awesome

chugging rhetorical power of the periodic sentence that cannot

go on forever even as it aspires to—the river channels water no longer,

not year-round. But the channel’s there, isn’t it, plain as a wide June

day, scrubbed clean in many parts and bristling with brush and trash

in others, hundreds of feet across at points, hemmed in mostly

by concrete culverts, effectively separating the city from the ritzier

homes and restaurants that populate the foothills. It separates via

space and threat of sudden flood surge, a reminder of the force of

water when it’s here, a reminder of the force we deploy in trying to

contain it, a reminder of the risk we take in ignoring it.

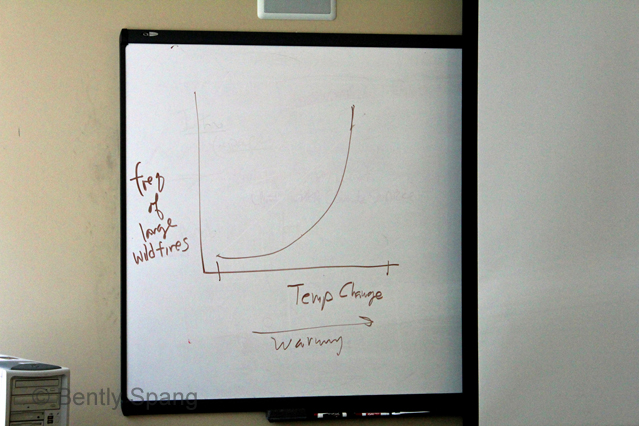

This year natural disasters have been everywhere, it seems. As I write

this, “Tornadoes kill 6 in Oklahoma, Kansas” (CNN ), and we’re less

than a week past the devastating tornado in Joplin, Missouri, not to

mention the more obvious man-aided nuclear disasters occurring

after the epic tsunami in Japan, the tornado system that removed both

of the places I lived in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, from the map a couple

weeks back, then the crazy freeze this winter in Tucson that killed

much of the saguaros though they won’t keel over for some years, their

death delayed, and then the massive floods in New Orleans, again, the

Red River in North Dakota, the eruption of Grimsvotn, the Icelandic

volcano whose ash cloud drift threatens to scuttle my summer travel.

My mother-in-law is freaked out about the end of the world prediction

that didn’t come to pass a couple weeks ago on May 21st, 2011, not

to mention the Mayan apocalypse predicted for next year, just to name

a few anxious highlights. I mean to say that the world’s tribulations are

present like weather in my mind, this month, going into the Tucson

monsoon season.

it’s everywhere: like nothing in the north except maybe a blizzard

surge or avalanche. The Rillito runs high when it storms, meeting and

joining the Santa Cruz and moving on north, bringing what benefits

water brings to the arid bits of West that it reaches less and less each

year. It is therefore possible to execute a water landing in Tucson at

least a dozen mostly monsoon days a year.

high like the river or cheerful, smelly Arizona stoners. I don’t know

what drives my spur to run: a fight against my own personal beltway

westward expansion, perhaps. A connection to a fitter vision, finer

version of myself. A bit of personal engineering: clawing some control

away from age and the natural tendency of the body.

computer; my animals when playful or fearful; machines; programmed

processes in machines; my nose in the dry air of the desert; coyotes,

rabbits, dogs, humans, lizards, and rare javelina through the wash in

the mornings when I run and spark their chase or flight; the blood

through the veins; the thoughts through the brain late at night when

they should be shutting down into easy, ecstatic dreams.

idle much of the time, though not to say empty or dry, exactly. After injury

or catastrophic change the channels reconfigure, find new ways to get the

signal through the network. (As aficionados of weird brain injuries know,

sometimes they don’t redirect so successfully.) Perhaps like desert denizens

they lay where it’s cool and await the occasional electrical impulse, at

which point they are signaled, woken and singing, alive.

only written after the songs were already in place.

songs. I imagine most musical theatre is built this way—songs first,

plot second, with some backfill as necessary. One structure is built to

accommodate—contain—control—another. That might account for

the odd plots of Gilbert & Sullivan, for instance.

H.M.S. Pinafore, Gilbert & Sullivan’s sea-set piece of musical theater

as it rains outside again: you can hear it on the roof. In Michigan

water’s abundance is an apparently incontrovertible fact. What is

Michigan if not a wet state, a water state? Bordered by four of the five

great lakes, Michigan’s vision of itself as a vacationland is no less dependent

on water than are the cities of the arid west. Fishing, boating,

beaches, tourism, even skiing, hunting, and snowmobile riding—these

are all built on water. Everything is lush, green, bushy, buggy, muggy,

prickled, itchy, and wet except when the state is blanketed by the

yearly onslaught of snow (still water, we’re reminded, when our frozen

boots melt on return in the house). Michigan is all coast, two peninsulas

separated and defined by water, settled by water, driven by water,

separated from Canada by water.

or snowbound landscapes of Michigan that still shape the way I think

and dream and write, and the hazy desert loneliness of Arizona, where

I now live and work.

double image, a composite of the two, product of both forms, that

compresses and elides the space between them.

channel itself, or the water that flows through it?

And is it navigable?

into) was ruled “navigable” by the Environmental Protection Agency,

thus making it eligible for protection under the federal Clean Water

Act. This followed the Army Corps of Engineers’ second-guessing

of their own ruling of “navigable” the previous May, which was then

withdrawn, in effect punting to the EPA. “Navigable” is a tricky word,

especially for the 90-95% of Arizona rivers that are dry for at least

part of the year. Calling a river “navigable” means more roadblocks for

developers wanting to build along the river. Calling a river “navigable”

enshrines it, embodies it as a river deserving administrative, environmental

protections. Calling a river “navigable” only if it runs yearround

brands a western river with the mark of the midwest or the east.

These notions don’t really apply here.

and, on the flipside, conservation effort depends on how we want

to parse the definition of river.

they’re geographical too; they shift and mutate as we do.

instance, the pagebreak is a designed absence, as is the gutterspace. I don’t

think about inhabiting it often, unlike margins, which lend themselves to

annotation, to notes on the marginal, aside from the text. Margins are for

our fingers, so we don’t obscure type with our Dorito-stained hands, so

our designed page can have a neat boundary in which it is contained.

The whitespace makes the text an island. Perhaps to conserve the

imaginative, associative space around a text, principles of classical

typography eschew using this space except as caesura.

off (and protects (and contains (perhaps like parentheses))) whatever

we define as the Rillito River.

through the city. Admittedly, much of that wildlife is now rare or missing,

not seen for decades. The following long list of species hasn’t been

seen in the Pantano Wash since the dates in parentheses: Northern

Goshawk (1999), Arizona Giant Skipper (1988), Poling’s Giant Skipper

(1967), Gila Longfin Dace (2004), Baird’s Sparrow (2003), Felder’s

Orange Tip (1992), Sabino Canyon Damselfly (1988), Giant Spotted

Whiptail (2005), Western Burrowing Owl (2004), Northern Gray

Hawk (1994), Common Black-Hawk (1977), Arizona Metalmark

(1993), Mexican Long-Tongued Bat (2005), Western Yellow-Billed

Cuckoo (2002), Pale Townsend’s Big-eared Bat (1986), Arizona Ridge-

Nosed Rattlesnake (1999), Northern Buff-breasted Flycatcher (2000),

Greater Western Bonneted Bat (2005), American Peregrine Falcon

(2005), Gila Chub (2004), Cactus Ferruginous Pygmy-Owl (1999),

Sonoran Desert Tortoise (2004), Western Black Kingsnake (2002),

Western Red Bat (2005), Lesser Long-Nosed Bat (2004), Obsolete

Viceroy Butterfly (1966), California Leaf-Nosed Bat (1986), Arizona

Myotis (1992), Cave Myotis (2001), Pocketed Free-tailed Bat (2005),

Big Free-Tailed Bat (2003), Texas Horned Lizard (1995), Gila Topminnow

(2004), Chiricahua Leopard Frog (2005), Lowland Leopard

Frog (2005), Yellow-nosed Cotton Rat (2003), Mexican Spotted Owl

(2004), and the Northern Mexican Gartersnake (2003).

A pause

or a permanence?

it when reading. How often do you think oh, the gutter, okay, this

to right, top to bottom in the western world, jump across the gutter in

page is done, so what do I do next? How often do you think yes, left

the center of the spread and onto the next block?

it’s given. The brain’s pathways accommodate this understanding. The

designer knows there is a visceral pleasure in reflowing prose blocks

in page design software like InDesign because she sets up channels

and adjusts the text box, watches the fluid dynamics work their magic.

Today she is an engineer. Today she is a small, beautiful god.

space from another’s, sunset from sunrise, the foothills from the city

of Tucson, St. Louis from East St. Louis, the west side from the east

side of Grand Rapids, Michigan; Iowa from Illinois; Missouri from

Illinois; liquid from solid from vapor; the cold from the not; the haves

from the nots; the darker-skinned from the lighter; Midwesterners

from Southerners; this list could go on as long as our culture. Rivers

are easy geographical borders, a shared feature, not part of what it

divides. Even when dry, those borders remain. The split between two

contiguous spaces remains. The brain sees a line.

the thalweg.

Flash Card 2: “The sinuosity of a channel is defined as the ratio between

the thalweg length and the down-valley distance” (Arizona Dept of Water Resources

Design Manual for Engineering Analysis of Fluvial Systems, 1985).

retains.

likely part to have water, whether runoff from precipitation on the

mountains or from sudden storm.

remaining thought resides when the rest evaporates or is washed or

erased or edited away.

deepest channel.

rivers will often (if not always) meander

the force of a turn eats further away at the bank; this increases until

it’s unsupportable, and it detaches into an oxbow

In an essay, “Meander,” that appeared in the very first issue of the journal

Creative Nonfiction, itself named for the recent American term to offer

some form to contain the formless, Mary Paumier Jones suggests that, like

the river, ocean currents also meander, as does the jetstream. That flow

itself seems to be best modeled not as straight but as swerve, at least under

certain conditions. That the river’s natural swerving is not

up on itself so as to fit more brain in a small space. And that the

essay—best simulation of the brain on the page we’ve got—its natural

motion, like the river’s, is meander.

essay of the same title that appeared in the journal Passages North and in the

2012 catalogue for the exhibit, Parallel Play: Interdisciplinary Responses to a

Dry River.

*

Parallel Play is funded by the Confluencenter for Creative Inquiry at the

University of Arizona.

*

ande r m on s on

o t h e r e l e c t r i c i t i e s . c o m